Great Tang Idyll

CH 28

on, you’ll sell this kind of paste sauce.

I’ll give you several recipes for dishes using this kind of paste sauce.

At the very least, you will sell 1 catty for 50 wen [cash].” Zhang Xiaobao also used a finger to dab up some sauce to taste it as he spoke to Song Jing-gong.

“No, that’s not it.

It was Little Mister.

Little Mister told me how to make it.

It wasn’t me.

It really wasn’t me.” Erniu had actually not tasted this sauce at all as once it had been made, he had brought it over.

So seeing Little Mister credit him for the work, he vigorously shook his head in denial.

Song Jing-gong, seeing the two people’s expressions and the words that they spoke, recalled the taste in his mouth once again as he said: “Little Mister, I, Song Jing-gong, really do admit defeat today.

I really do.

There’s credit that you don’t claim and you can still make this kind of delicious item.

You can relax; I’ll sell it at 100 wen [cash] per catty for you.”

“Don’t.

If you really sell it that expensively, then that would be cheating me.

You can only sell it at 50 wen [cash] for 1 catty.

Wait until I’ve produced the soybean oil and it’s been stir-fried in oil afterwards—then, we can sell it for 100 wen [cash].

We’re doing legitimate business.

We don’t need to swindle.”

Zhang Xiaobao, upon seeing Song Jing-gong’s appearance, knew what he was thinking and instantly rejected this suggestion.

Then, looking at Erniu, he said: “Now, I’m giving you a new mission.

Add the soybean bits [douban] inside the sauce.

Categorize this and the previous one into two kinds of sauces.

Remember to keep it secret.”

“Little Mister, you [honorific] rest assured as I, Erniu, will certainly complete this matter.

I’ll go then.” After he finished speaking, Erniu turned around and left.

Song Jing-gong used his hand to scoop up some meat from inside the sauce to place it on his tongue as he asked: “Why is there a special flavor? It seems to be spicy.”

“It’s the same as that formula for hatching chicks that you had bought.

You always need something better in order to sell something worse.” Zhang Xiaobao said, smiling.

Juan-Juan says “ming qian” (明前) in Chinese here, which literally means “before light” and refers to “ming qian cha” (明前茶) or “before light tea” that itself is a shorthand name for tea that was picked before the Qingming Festival (清明節) as it is believed that tea leaves picked afterward don’t compare in taste to the tea leaves picked before the festival.

Therefore, pre-festival tea leaves tend to be exponentially more expensive and valued than tea leaves picked post-festival.

Juan-Juan stating that the tea is too old means that the tea leaves were picked later as they had time to grow more and thus, are not as tender as they could have been if they had been picked earlier.

“Heng tie bu cheng gang” (恨鐵不成鋼) is an expression in Chinese that uses the analogy of iron and the hard work required to turn it into steel as the metallurgic technology wasn’t advanced enough back then to guarantee that iron could be successfully forged into steel.

So someone who hates that the iron hadn’t turned into steel is usually metaphorically expressing frustration that someone with great potential is wasting it.

This idiom is especially apt if the person so frustrated is the metaphorical smith who has put a lot of effort into nurturing or transforming the wasted talent that is being likened to the iron ore that failed to turn into steel.

“Zhong yang” (中庸) translates to “moderation” and refers to the Confucian philosophy, “zhong yang zhi dao” (中庸之道 ), which means “path of moderation” though it has been translated as “Doctrine of the Mean” in English.

It is also the title of one of the Four Books of Confucianism.

It shares remarkable similarities to the Greek philosophical idea of the “Golden Mean” as posed by Aristotle and the Buddhist concept of the Middle Way or “zhong dao” (中道) in that all three approaches basically argue for avoiding excess or extremes and sticking to the middle.

“Mu liao” (幕僚) roughly means “aide” but it is a term that doesn’t refer to the typical peon assistant or aide and has an added connotation of an advisory background role that is granted a great deal of independence and trust in order to work toward their leader’s goal.

For the sake of reference, the title of White House Chief of Staff is translated into Chinese as “Bai Gong Mu Liao Zhang” (白宮幕僚長) as the White House staff are essentially the President’s personal advisory aides who’d help with anything that impacted the President as an individual politician versus the national advisors who would give advice on official national policy but wouldn’t normally deal with the personal politics of the President.

So Xiaobao is basically asking Song Jing-gong to not only be his assistant but also act as an independent personal advisor.

This term comes up a lot in historical Chinese fiction because these “mu liao” could be collected into a group to become an ancient form of think tank or advisory team for their lord and acted as key players if there were any backroom dealings or conspiracies to scheme over and put into action.

For example, one of the most famous geniuses in Chinese history and culture, Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮), was essentially one of these for Liu Bei (劉備) before he was promoted to Chancellor after the state of Shu Han (蜀漢) was founded during the Three Kingdoms period.

“Xue wu zhi jing” (學無止境) is a 4-character couplet that can be traced back to a Qing dynasty text, “Wen Shuo” 《問說》 by Liu Kai (劉開).

Likely, the author didn’t realize that this was anachronistic so let’s just pretend Song Jing-gong is unwittingly ahead of his time…

The 4-character idiom “dazhe wei shi” (達者為師) is another one of those mnemonic phrases that don’t make complete sense until you consider the entire context that it is taken from.

Taken literally, it means “the one who reaches it becomes a teacher,” which is a bit nonsensical.

The full sentence is “學無前後,達者為先” and is from the Tang dynasty text, “Shi Shuo” 《師說》 by Neo-Confucian poet Han Yu (韓愈).

The latter half makes more sense when you combine it with the former half’s meaning, which translates to “learning has no first or last.” This expression basically espouses the thinking that those who are the best or most skilled should be respected regardless of seniority, an idea that is slightly heretical to the respect given to the age hierarchy in traditional Confucianism as it encourages the possibility of an older or more senior person deferring to a younger or more junior person if they possess the necessary learning or skill.

Thus, it’s essentially promoting a version of “survival of the fittest” within scholarly circles in that the most learned ones should become teachers, regardless of age or seniority.

“Dazhe” (達者) became a synonym for “capable one or expert” because of this quote even though it technically just means “arrived one.” Song Jing-gong essentially modified this sentence so that the meaning is slightly changed to show that he is acknowledging the children’s fitness to be his master and teacher.

“Zhuge” (諸葛) is the surname of Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮), who is commonly considered the epitome of genius and intelligence in Asia due to the essential role that he played as the strategist for Liu Bei (劉備) and the state of Shu Han (蜀漢) during the Three Kingdomsperiod as well as the inventions attributed to him.

This status is also helped by the fact that the novelization of the historical events of the Three Kingdoms is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms or “San Guo Yanyi” 《三國演義》, that took artistic license to expound greatly on Zhuge Liang’s cunning and exploits.

It is easy to know that Zhuge Liang is being referenced when just using the surname since it is rare to have 2-character surnames (also known as compound surnames) in China, much less the particular one of Zhuge.

The Chinese used here of “tie xue shou duan” (鐵血手段), I translated literally.

I am footnoting it because I had to suppress the urge to translate it as blood and steel since steel is the metal mentioned whenever an euphemism for weapons is used in English whereas iron is the metal that always shows up in the Chinese language as a symbol for weapons or war.

This is likely because the Chinese literary customs ossified and forever tied iron with war, even after the Chinese had already discovered ways to produce steel although steel wasn’t produced in enough mass quantities to have entire armies outfitted in them.

This is probably similar to how English idioms will still mention swords in metaphors even though they are no longer in common use, having been superseded in their role by guns.

I translated “qing jia dang chan” (傾家盪產) as “bankruptcy and ruin” but it actually literally translates to “collapse of house, rocking of production,” which basically means loss of home (homelessness) and financial loss or instability.

Guan Zhong (管仲) was the chancellor of the state of Qi (齊) during the Spring and Autumn period who was thought to be the ideal minister and was greatly praised by Confucius.

His efforts made his state the most powerful of the feudal states in China at the time.

“Zijin” (子衿) isn’t actually a real word but is the title of a poem.

So this would be similar to someone taking on an internet alias or pseudonym based on a song or book.

Zi/子 is a multi-purpose character that has a variety of meanings depending on the situation and in this case, it is likely acting as a placeholder word for person or individual.

Jin/衿 refers to the collar or lapel that diagonally traverses the front of a Hanfu (漢服) garment.

Because of the export of Chinese clothing styles over time through the Sinosphere, you can see this collar style reflected in the design of the traditional Japanese kimono (きもの/着物) or Korean hanbok (한복/韓服) as well.

Zi/字 literally means “character” but in this case, it is referring to the style or courtesy namethat an educated man assumes upon reaching his majority at the age of 20.

Biao/表 (meaning appearance) is also another way to refer to this name in Chinese.

This style or courtesy name was reserved for intimates or close friends to use in ancient China while those who weren’t, used the person’s titles or surname to address them.

A person’s given name was hardly ever used except for in legal documentations since even family members tended to either use nicknames and pet names or family titles to address them by, a practice that was likely a culmination of various Chinese naming customs and an extension of the thinking that doing so would possibly draw too much attention from malevolent spirits who would be able to identify the person by their true name.

The quote of “qing qing zijin, you you wo xin” (青青子衿,悠悠我心) comes from an anthology of classical Chinese poetry called “Shijin” 《詩經》 or the Classic of Poetry—namely, it is from a poem titled “Zijin” (子衿) from the “Zheng Feng” (鄭風) or the Odes toZheng section of the “Airs of the States” (Guo Feng/國風) part of the compilation.

The poem’s subject is about a man waiting in the upper story of a building for his close friend or lover (there has been some historical debate over the actual nature of the relationship).

This particular phrase was then quoted by the Three Kingdoms period warlord and founder of the state of Cao Wei (曹魏), Cao Cao (曹操), in a well known yuefu (樂府) style poem of his that he composed right before the Battle of Red Cliffs (赤壁之戰) that was titled “Duan Ge Xing” 《短歌行》 or Short Song Style in order to express his passionate longing for collecting talented people under his flag.

For those wondering why it sounds like it could be a song lyric, it is because yuefu style poems are composed to resemble music.

“Bing” (餅) translates to “cake, bread, biscuit, or cookies” depending on the context.

Because the food item in question here is a flattened and round cake made out of unleavened dough that is similar to flatbreads and pancakes (in fact, scallion pancakes are a fried type of these), I chose to translate this food item as “flat cake” in English.

For other similar foods, compare Mexican tortillas, Indian roti, or French crêpes.

You'll Also Like

-

The Most Popular Comedian

Chapter 65 September 3, 2023 -

Red Envelope Group of the Three Realms

Chapter 1986 September 1, 2023 -

Reverse Domestication

Chapter 39 September 2, 2023 -

The Taste Of Apple Jam

Chapter 9 August 29, 2023 -

Using Gacha to Increase My Companions and to Create the Strongest Girls’ Army Corps

Chapter 84 August 28, 2023 -

In Order To Meet You, Beloved

Chapter 35 August 28, 2023 -

Disciplinary Code

Chapter 65 September 4, 2023 -

The Cat Transformation

Chapter 27 August 26, 2023 -

Chemistry

Chapter 61 August 25, 2023 -

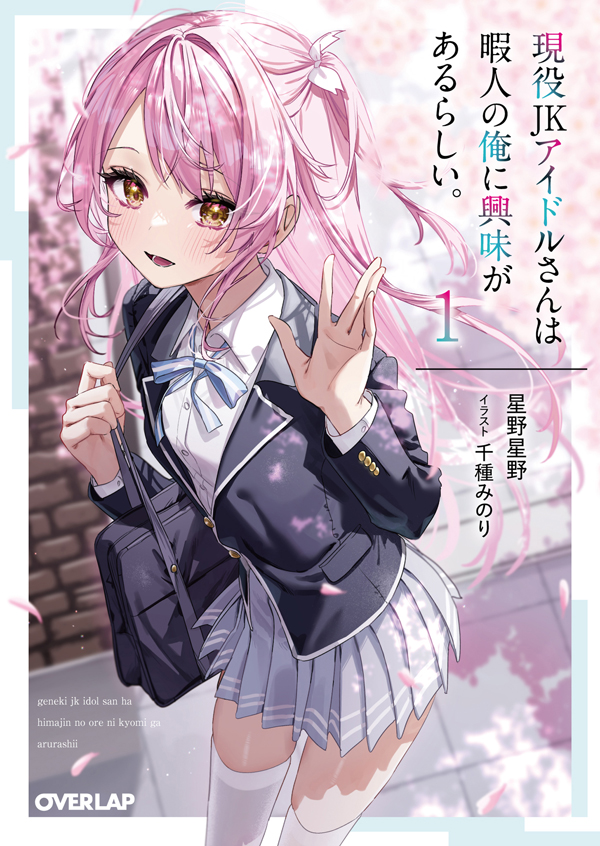

Active JK Idol Seems to be Interested in Me Who is a Free Person.

Chapter 32 August 25, 2023 -

After Being Robbed of Everything, She Returns as a Goddess

Chapter 47 August 25, 2023 -

The Marquis’ Eldest Son’s Lascivious Story

Chapter 232 August 26, 2023